More importantly and enjoyable for me was our discussion about Tom Thomson (1877-1917) an Owen Sound native, artist and sportsman. He was intimately involved with the Canadian group of painters called The Seven and is an artist I have followed and been a fan of for many years. My comment that, "one of the reasons I love Tom, and most of the Canadian, early 20th century painters is that their work has a certain Arts and Crafts esthetic that really moves me" was well-received by Virginia. She explained further that most of the backgrounds the painters had were in design and they were in fact influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement. Unfortunately our time was limited but the visit was great.

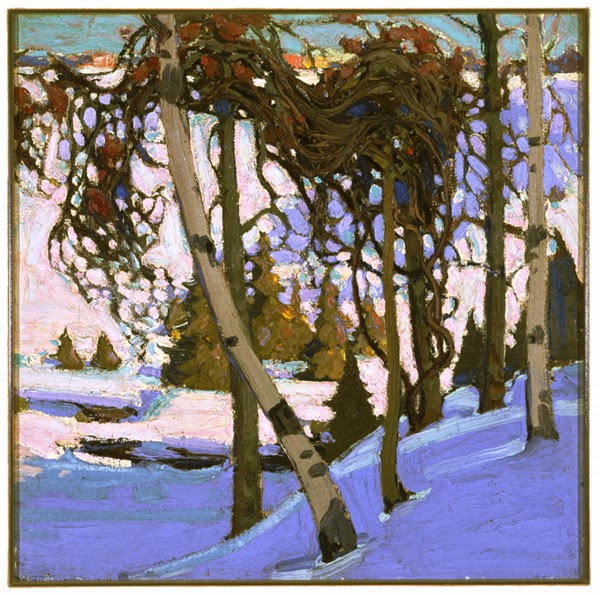

Early Snow, 1916

oil on canvas

45.5 x 45.5 cm

Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery; Acquired with the

assistance of a grant from the Canadian Government, approved by the

Minister of Canadian Heritage under the terms of the Cultural Property

Export and Import Act, and with contributions by The Winnipeg

Foundation, The Thomas Sill Foundation Inc., The Winnipeg Art Gallery

Foundation Inc., Mr. and Mrs. G.B. Wiswell Fund, DeFehr Foundation Inc.,

Loch and Mayberry Fine Art Inc, and several anonymous donors.

Thomson was raised on the farm and received his education locally, though ill health kept him out of school for a period of time. He was said to have been enthusiastic about sports, swimming, hunting and fishing. He shared his family’s sense of humour and love of music.

Indeed, Tom’s Victorian upbringing, gave him an immense appreciation

for the arts. Drawing, music, and design were valuable and honoured

pursuits. Within this Scottish family structure, however, there were

also pressures to succeed, to find an occupation, to marry, and to have a

family.

Indeed, Tom’s Victorian upbringing, gave him an immense appreciation

for the arts. Drawing, music, and design were valuable and honoured

pursuits. Within this Scottish family structure, however, there were

also pressures to succeed, to find an occupation, to marry, and to have a

family.Tom had a restless start to his adulthood. Unsuccessful at enlisting for the Boer War in 1899 due to health reasons, Tom apprenticed as a machinist at Kennedy’s Foundry in Owen Sound for 8 months. Still undecided on a career, he briefly attended business school in Chatham. In 1901, he moved to Seattle, Washington to join his brother George at his business college. Here he became proficient in lettering and design, working as a commercial artist during the next few years. By 1905, he had returned Canada to work as a senior artist at Legg Brothers, a photo-engraving firm in Toronto. Tom continued to return home to visit his family his entire life, though his parents had, by this time, sold the farm in Leith, and moved to a house in Owen Sound.

In 1909 Thomson joined the staff of Grip Ltd., a prominent Toronto photo-engraving house, and this proved to be a turning point in his life. The firm’s head designer, artist-poet J.E.H. MacDonald, contributed much to Thomson’s artistic development, sharpening his sense of design. Fellow employees included Arthur Lismer, Fred Varley, Franklin Carmichael and Franz Johnson – all adventurous young painters who often organized weekend painting trips to the countryside around Toronto. After Tom’s death, these men, together with Lawren Harris and A.Y. Jackson, would go on to form Canada’s first national school of painting, the Group of Seven.

Curator Charles Hill comments that “Thomson’s surviving artwork prior

to 1911 consists of drawings in ink, watercolour and coloured chalk, of

women’s heads very much in the vein of the American illustrator Charles

Dana Gibson, who had established the “Gibson girl” look, as well as ink

and watercolour landscapes done around Leith, Owen Sound and Toronto

and illuminated text presented as gifts to members of his family or

friends.” He also states “The arrangements of some texts and designs has

a similarity to the patterning of stained glass and are most likely

characteristic of the Arts and Crafts-influenced commercial work he

might have done.”

Curator Charles Hill comments that “Thomson’s surviving artwork prior

to 1911 consists of drawings in ink, watercolour and coloured chalk, of

women’s heads very much in the vein of the American illustrator Charles

Dana Gibson, who had established the “Gibson girl” look, as well as ink

and watercolour landscapes done around Leith, Owen Sound and Toronto

and illuminated text presented as gifts to members of his family or

friends.” He also states “The arrangements of some texts and designs has

a similarity to the patterning of stained glass and are most likely

characteristic of the Arts and Crafts-influenced commercial work he

might have done.”In 1912, inspired by tales of Ontario’s “far north”, Thomson traveled to the Mississagi Forest Reserve near Sudbury, and to Algonquin Park, a site that was to inspire much of his future artwork. It was during this same year that Thomson began to work for the commercial art firm Rous and Mann.

He was joined there by Varley, Carmichael and Lismer. Later the same year, at J.E.H. MacDonald’s studio, Thomson met art enthusiast Dr. James MacCallum, a prominent Toronto Ophthalmologist.

When out painting on location, Thomson would use a small wooden sketch box, not much bigger then a piece of letter-sized paper, to carry his oil paints, palette, and brushes; his small painting boards were safely tucked away from each other in slots fitted in the top. Sitting down in the canoe, on a log or rock, with the sketch box in front of him, he would quickly capture the landscape around him.

In 1913 Thomson exhibited his first major canvas, A Northern Lake, at the Ontario’s Society of Artists exhibition. The Government of Ontario purchased the canvas for $250 a considerable sum in 1913, considering Thomson’s commercial artist’s weekly salary was $35 in 1912. That same year, Dr. James MacCallum guaranteed Thomson’s expenses for a year, enabling him to devote all his time to painting. Taking leave from his work as a commercial artist, Thomson returned north.

Thomson’s home base when he visited Algonquin was Mowat Lodge, a small hotel in the tiny community of Mowat at the north end of Canoe Lake. Thomson would stay at the Lodge in the early spring, as he waited for the lakes and rivers to break up before he would go camping, and again in the late fall. Painting and fishing competed for his attentions in the park. He was not only an active guide for his colleagues from Toronto, but also for other summer park visitors.

From a letter Tom sent to Dr. MacCallum from Camp Mowat, on October 6, 1914, Tom wrote: “Jackson and myself have been making quite a few sketches lately and I will send a bunch down with Lismer when he goes back. He & Varley are greatly taken with the look of things here, just now the maples are about all stripped of leaves but the birches are very rich in colour. We are all working away but the best I can do does not do the place much justice in the way of beauty.”

Charles Hill notes that it appears that painting was not something Thomson learned easily, and the process was accompanied by much self-doubt. Jackson recounted that in the fall of 1914 in Algonquin Park Thomson threw his sketch box into the woods in frustration. Jackson claimed that Thomson “was so shy he could hardly be induced to show his sketches.”

War had broken out in Europe in summer of 1914. Thomson was not able to enlist due to health reasons, but many of his artist friends and colleges did, or went overseas to work as war artists.

From 1914 to 1917 Thomson spent the spring and fall sketching, and

acted as a guide and fire Ranger during the summer in Algonquin Park. He

became an expert canoeist and woodsman. He spent the winter in

“Thomson’s Shack”, a construction shed outside the Studio Building in

Toronto. It was here where he painted his now famous canvases, The Jack

Pine, The West Wind, and Northern River, among others.

This was a time of great change in the world with the First World War

raging in Europe. As Thomson continued to paint in the North, he become

interested in the subtle changes all around him. Thomson documented

changes in the season, shifts in the weather and changes in the light

over the day; for him these were exciting changes.

This was a time of great change in the world with the First World War

raging in Europe. As Thomson continued to paint in the North, he become

interested in the subtle changes all around him. Thomson documented

changes in the season, shifts in the weather and changes in the light

over the day; for him these were exciting changes.

Many of Thomson’s paintings from Georgian Bay and Algonquin Park strike an interesting balance; his imagery is at once innovative, but rooted in careful observation. His artwork changed dramatically: from painting every detail in an almost photographic manner in his earlier work, to capturing the true spirit of the landscape around him. Within a six-year period, he had developed a strong personal style of bold colour combinations, expressive brush strokes and unique images of the Northern landscape.

Art historians have noted that Thomson paintings from this period show the artist’s appreciation of the rugged beauty of Algonquin Park. The bold immediacy of Thomson’s sketches was to define a new style of painting that would be attributed as uniquely Canadian and would shape how generations of people think about the Canadian landscape.

Thomson was able to convey the dynamism and volatility of nature,

breaking away from the traditional detail style of painting in his

earlier works, to bold splashes of colour and non traditional

compositions. His paintings came to suggest the drama of the woodland,

and the forces of nature on the forests and lakes.

Thomson was able to convey the dynamism and volatility of nature,

breaking away from the traditional detail style of painting in his

earlier works, to bold splashes of colour and non traditional

compositions. His paintings came to suggest the drama of the woodland,

and the forces of nature on the forests and lakes.

Thomson found beauty in the most uncommon scenes – Jackson wrote: “To most people Thomson’s country was a monotonous dreary waste, yet out of one little stretch he found riches undreamed of. Not knowing all the conventional definitions of beauty, he found it all beautiful: muskeg, burnt and drowned land, log chutes, beaver dams, creeks, wild rivers and placid lakes, wild flowers, northern lights, the flight of wild geese and the changing seasons from spring to summer to autumn.”

These were important times spent in Algonquin, bringing together Thomson and his fellow artists to exchange ideas, techniques, stories and philosophies, and inevitably building strong collegial bonds. Thomson’s confidence as a painter really developed during these years, encouraged and coaxed along by his peers. Thomson, the man, also found peace. He was seeking freedom from the repressive confines of Victorian family life, and escape from the hustle and bustle of Toronto’s art world where he never quite fit in. It was in the solitude of Algonquin’s lakes and woods that he became himself.

Tom Thomson died sometime between July 8, when he was last seen, and July 16, 1917, when his body was found floating in Canoe Lake. The cause of death was recorded as accidental drowning.

On Monday, July 16, Dr. G.W. Howland, a Toronto physician and professor of neurology at the University of Toronto, saw an unidentifiable object lying in the water some yards from the shore. Dr. Howland asked two local guides, George Rowe and Lourie Dickson, who were on the water at the time, to investigate. They found Tom’s body.

Tom would have celebrated his fortieth birthday on August 5. His watch had stopped at 12:14. Dr. Howland was asked to examine the body before burial. He reported a bruise about 10 cm across the right temple, air issuing from the lungs, and some bleeding from the right ear. And though his death was officially recorded as accidental due to drowning, his demise has become one of Canada’s greatest mysteries.

Thomson was initially buried in a small cemetery up the hill from Mowat Lodge, overlooking Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. But at the request of his family, the body was reinterred in the family plot beside Leith United Church.

In September of 1917, J.E.H. MacDonald, Dr. MacCullum and J.W. Beatty built a stone cairn on Hayhurst Point, overlooking Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park, close to one of Tom Thomson’s favourite camp sites across from the bay from Mowat. The cairn is a memorial to Thomson, marking the date and the place where he had died. Thomson’s death was a tragedy for his fellow artists – they lost an inspiring colleague, a great friend and their guide to the north woods. This untimely loss prompted a clarification of his artist friends’ vision for Canadian art; it strengthened their resolve and gave rise to the formation of The Group of Seven.

The cairn’s inscription was composed by Thomson’s friend, painter J. E. H. MacDonald, and reads:

The following brief Biography has been developed by David Huff, Manager of Public Programs at the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound. The material has been compiled from various sources, including the Gallery archives, Charles Hill, Joan Murray and Stuart Reid.

(Photos and text courtesy of The Tom)

(All photos of Tom Thomson paintings are courtesy of Wiki Art)

Click below for a look at the incredible work of Tom Thomson

This was a time of great change in the world with the First World War

raging in Europe. As Thomson continued to paint in the North, he become

interested in the subtle changes all around him. Thomson documented

changes in the season, shifts in the weather and changes in the light

over the day; for him these were exciting changes.

This was a time of great change in the world with the First World War

raging in Europe. As Thomson continued to paint in the North, he become

interested in the subtle changes all around him. Thomson documented

changes in the season, shifts in the weather and changes in the light

over the day; for him these were exciting changes.Many of Thomson’s paintings from Georgian Bay and Algonquin Park strike an interesting balance; his imagery is at once innovative, but rooted in careful observation. His artwork changed dramatically: from painting every detail in an almost photographic manner in his earlier work, to capturing the true spirit of the landscape around him. Within a six-year period, he had developed a strong personal style of bold colour combinations, expressive brush strokes and unique images of the Northern landscape.

Art historians have noted that Thomson paintings from this period show the artist’s appreciation of the rugged beauty of Algonquin Park. The bold immediacy of Thomson’s sketches was to define a new style of painting that would be attributed as uniquely Canadian and would shape how generations of people think about the Canadian landscape.

Thomson was able to convey the dynamism and volatility of nature,

breaking away from the traditional detail style of painting in his

earlier works, to bold splashes of colour and non traditional

compositions. His paintings came to suggest the drama of the woodland,

and the forces of nature on the forests and lakes.

Thomson was able to convey the dynamism and volatility of nature,

breaking away from the traditional detail style of painting in his

earlier works, to bold splashes of colour and non traditional

compositions. His paintings came to suggest the drama of the woodland,

and the forces of nature on the forests and lakes.Thomson found beauty in the most uncommon scenes – Jackson wrote: “To most people Thomson’s country was a monotonous dreary waste, yet out of one little stretch he found riches undreamed of. Not knowing all the conventional definitions of beauty, he found it all beautiful: muskeg, burnt and drowned land, log chutes, beaver dams, creeks, wild rivers and placid lakes, wild flowers, northern lights, the flight of wild geese and the changing seasons from spring to summer to autumn.”

These were important times spent in Algonquin, bringing together Thomson and his fellow artists to exchange ideas, techniques, stories and philosophies, and inevitably building strong collegial bonds. Thomson’s confidence as a painter really developed during these years, encouraged and coaxed along by his peers. Thomson, the man, also found peace. He was seeking freedom from the repressive confines of Victorian family life, and escape from the hustle and bustle of Toronto’s art world where he never quite fit in. It was in the solitude of Algonquin’s lakes and woods that he became himself.

Tom Thomson died sometime between July 8, when he was last seen, and July 16, 1917, when his body was found floating in Canoe Lake. The cause of death was recorded as accidental drowning.

On Monday, July 16, Dr. G.W. Howland, a Toronto physician and professor of neurology at the University of Toronto, saw an unidentifiable object lying in the water some yards from the shore. Dr. Howland asked two local guides, George Rowe and Lourie Dickson, who were on the water at the time, to investigate. They found Tom’s body.

Tom would have celebrated his fortieth birthday on August 5. His watch had stopped at 12:14. Dr. Howland was asked to examine the body before burial. He reported a bruise about 10 cm across the right temple, air issuing from the lungs, and some bleeding from the right ear. And though his death was officially recorded as accidental due to drowning, his demise has become one of Canada’s greatest mysteries.

Thomson was initially buried in a small cemetery up the hill from Mowat Lodge, overlooking Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. But at the request of his family, the body was reinterred in the family plot beside Leith United Church.

In September of 1917, J.E.H. MacDonald, Dr. MacCullum and J.W. Beatty built a stone cairn on Hayhurst Point, overlooking Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park, close to one of Tom Thomson’s favourite camp sites across from the bay from Mowat. The cairn is a memorial to Thomson, marking the date and the place where he had died. Thomson’s death was a tragedy for his fellow artists – they lost an inspiring colleague, a great friend and their guide to the north woods. This untimely loss prompted a clarification of his artist friends’ vision for Canadian art; it strengthened their resolve and gave rise to the formation of The Group of Seven.

The cairn’s inscription was composed by Thomson’s friend, painter J. E. H. MacDonald, and reads:

TO THE MEMORY OF TOM THOMSON ARTIST, WOODSMAN AND

GUIDE WHO WAS DROWNED IN CANOE LAKE JULY 8TH, 1917

GUIDE WHO WAS DROWNED IN CANOE LAKE JULY 8TH, 1917

HE LIVED HUMBLY BUT PASSIONATELY WITH THE WILD

IT MADE HIM BROTHER TO ALL UNTAMED THINGS OF NATURE

IT DREW HIM APART AND REVEALED ITSELF WONDERFULLY TO HIM

IT SENT HIM OUT FROM THE WOODS ONLY TO SHOW THESE REVELATIONS THROUGH HIS ART AND IT TOOK HIM TO ITSELF AT LAST.

The interest in Tom Thomson, the man, his art and the myth has

increased dramatically over the years since his death. The people of

Owen Sound named their new civic art gallery to honour Thomson in 1967.

With strong support from the Thomson family, the Gallery’s collection of

Tom Thomson’s artwork has grown over the years to become of national

significance. Visitors from around the world travel every year to visit

the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound to see the exquisite

collection of works and memorabilia of one of Canada’s greatest mythic

figures.The following brief Biography has been developed by David Huff, Manager of Public Programs at the Tom Thomson Art Gallery in Owen Sound. The material has been compiled from various sources, including the Gallery archives, Charles Hill, Joan Murray and Stuart Reid.

(Photos and text courtesy of The Tom)

(All photos of Tom Thomson paintings are courtesy of Wiki Art)

Click below for a look at the incredible work of Tom Thomson

It was great visiting you and chatting about art yesterday Parker! Hope you'll have a chance to visit the TOM one day soon. Best, V.

ReplyDelete