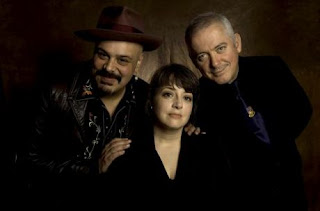

It seems rather odd that I had not ran across this amazing cover of this Magnetic Fields song. But I did and thats all that matters. The Pine Valley Cosmonauts are an ever changing group of super talented Nashville and Austin musicians with roots in Americana and traditional country music. Jon Langford is one of the founders and also one of my very favorite outsider artists. His art can be found at Yard Dog Art Gallery in Austin. The band also includes Bobby Bare Jr.

Kelly Hogan is simply amazing. Here is a bit about her from her record labels website:

Kelly's voice is so versatile it can wrap itself around any song, in any style, be it torchy jazz, country weepers, soul-fueled bump and grinders or long-lost pop nuggets, and transform them into something all her own. Hell, just her compilation appearances could be their own "Best of..." collection. She's that good. Like the Heat Miser, whatever she touch, becomes too much, and starts to melt in her clutch...I mean, she covers a haunting, chilling, world-ending ballad like "I'll Go To My Grave Loving You" on Because It Feel Good AND turn the kids' bath time diddy "Rubber Duckie" from The Bottle Let Me Down into a steamy, sexed-up invite...now THAT'S versatility. Think of her music as existential countrypolitan soul with a world class voice.

Kelly was born and raised in Atlanta where her dad is a policeman and her mom can make a pickle out of anything. She's been singing as long as she can remember. Her brother used to punch her in the arm for constantly harmonizing with the radio, yet she could not put a sock in it. Hogan began to hone her mellifluously spooky welter of torch songs and honky tonk anthems when she fronted the legendary peg-legged cabaret quartet, The Jody Grind, and then fanned the flames of her bummer-rock fixation while playing guitar for Orbisonic southern gothic punks, The Rock*A*Teens. Then she got ants in her pants and she moved north to Chicago in 1997 where she became Bloodshot's first paid employee ($500 a month!). After Bloodshot Rob saw her get up and sing with Dale Watson at Schubas, he promptly fired her and demanded she get back to singing.

Her stint in our busy little hive was marked by two solo albums, appearances on some clever and popular Bloodshot compilations, a split single with fellow dirtybird Neko Case, and appearances on albums by the Sadies, Nora O'Connor, the Pine Valley Cosmonauts, Wee Hairy Beasties, Rex Hobart & the Misery Boys, Robbie Fulks, Roger Knox, Jon Langford, Alejandro Escovedo and, are we missing somone? Probably. Everybody wants Kelly on their records.

To whit, the past few years has seen Kelly singing with fellow Georgians the Drive-By Truckers, gospel legend Mavis Staples, Iron and Wine, Jakob Dylan, the hopped up jazz combo The Wooden Leg and recording and touring with Neko Case as her back up singer (a match made in heaven, let us tell you). There's prolly a lot more we're missing, but we can guarantee if Hogan is on it or with it, you're gonna love it.

Kelly Hogan is simply amazing. Here is a bit about her from her record labels website:

Kelly's voice is so versatile it can wrap itself around any song, in any style, be it torchy jazz, country weepers, soul-fueled bump and grinders or long-lost pop nuggets, and transform them into something all her own. Hell, just her compilation appearances could be their own "Best of..." collection. She's that good. Like the Heat Miser, whatever she touch, becomes too much, and starts to melt in her clutch...I mean, she covers a haunting, chilling, world-ending ballad like "I'll Go To My Grave Loving You" on Because It Feel Good AND turn the kids' bath time diddy "Rubber Duckie" from The Bottle Let Me Down into a steamy, sexed-up invite...now THAT'S versatility. Think of her music as existential countrypolitan soul with a world class voice.

Kelly was born and raised in Atlanta where her dad is a policeman and her mom can make a pickle out of anything. She's been singing as long as she can remember. Her brother used to punch her in the arm for constantly harmonizing with the radio, yet she could not put a sock in it. Hogan began to hone her mellifluously spooky welter of torch songs and honky tonk anthems when she fronted the legendary peg-legged cabaret quartet, The Jody Grind, and then fanned the flames of her bummer-rock fixation while playing guitar for Orbisonic southern gothic punks, The Rock*A*Teens. Then she got ants in her pants and she moved north to Chicago in 1997 where she became Bloodshot's first paid employee ($500 a month!). After Bloodshot Rob saw her get up and sing with Dale Watson at Schubas, he promptly fired her and demanded she get back to singing.

Her stint in our busy little hive was marked by two solo albums, appearances on some clever and popular Bloodshot compilations, a split single with fellow dirtybird Neko Case, and appearances on albums by the Sadies, Nora O'Connor, the Pine Valley Cosmonauts, Wee Hairy Beasties, Rex Hobart & the Misery Boys, Robbie Fulks, Roger Knox, Jon Langford, Alejandro Escovedo and, are we missing somone? Probably. Everybody wants Kelly on their records.

To whit, the past few years has seen Kelly singing with fellow Georgians the Drive-By Truckers, gospel legend Mavis Staples, Iron and Wine, Jakob Dylan, the hopped up jazz combo The Wooden Leg and recording and touring with Neko Case as her back up singer (a match made in heaven, let us tell you). There's prolly a lot more we're missing, but we can guarantee if Hogan is on it or with it, you're gonna love it.