Hazel Home Art and Antiques Wausau, Wisconsin

Showing posts with label chicago. Show all posts

Showing posts with label chicago. Show all posts

Saturday, July 11, 2015

Monday, May 4, 2015

Rare turn of the century salemans sample apartment size grand piano for The Lyons and Healy Company, Chicago Illinois.

Here's something I had never seen before. Tiny metal grand piano stamped Lyons & Healy Chicago on the front above the keyboard. On the bottom it is stamped Rehderger Mfg. Co. Chicago. As I have mentioned in other posts, for most of the 20th century Chicago was the center of musical instrument manufacturing and retail business in the United States. In the loop alone were over 100 music stores, some buildings had 20-30 stores in them. Everything from stringed instruments, horns and pianos were made in Chicago. This is the first salesman's sample for a baby grand that I have ever seen. They marketed it as an apartment size grand piano. This piece is only about 4" x 3 1/2" x 3" and is in it's original brown paint. Condition is excellent. It is available for purchase here

Click below for the history of Lyon & Healy.

Click below for the history of Lyon & Healy.

Tuesday, April 21, 2015

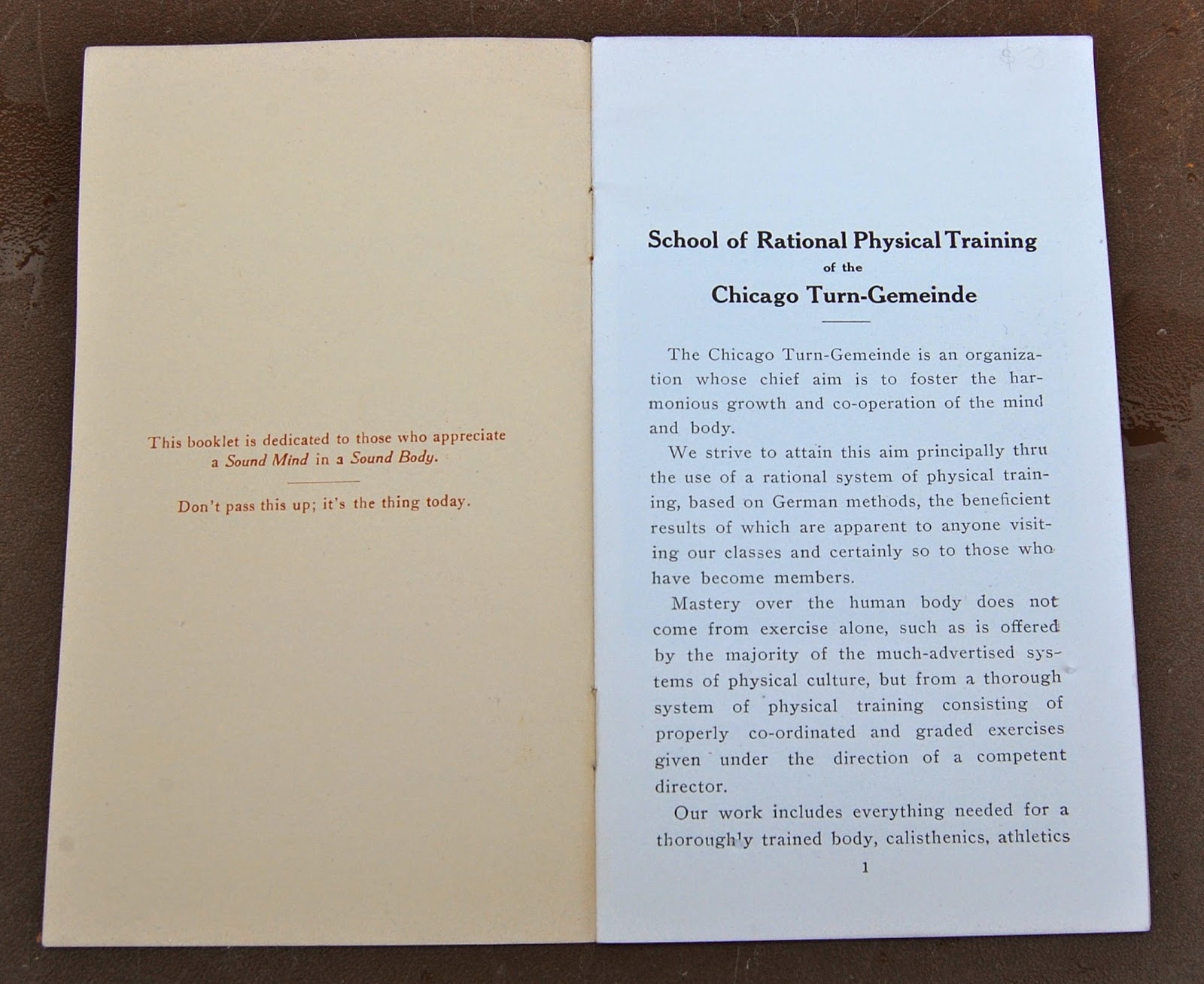

"Building a Sound Mind and a Sound Body" The Turner Movement in Chicago (1850-1950)

This morning I was looking at an interesting piece of early Chicago ephemera. A general information booklet for The Chicago Turn-Gemeinde School for Physical Training, North Side Turner Hall, 820 North Clark Street, Chicago. A Turner Hall was a gymnasium, theater and social club for German immigrants. Their belief was that a strong mind and body will provide everything a man needed to survive in his new home, the United States.

Besides physical training, the building of the mind took on an extremely politicized ideal that was very pro-union and anti-business. Much of Chicago's progressive movement grew out of these Socialist clubs. As I understand it, today, the few remaining Turners are strictly sports oriented particularly in youth activities in the historic German neighborhoods. Soccer, basketball, volleyball, ice hockey and baseball have replaced calisthenics, gymnastics, fencing, medicine balls and Indian Clubs. I particularly like the advertisement for a sporting goods store inside the back cover. The proprietor is holding a fencing epee.

Besides physical training, the building of the mind took on an extremely politicized ideal that was very pro-union and anti-business. Much of Chicago's progressive movement grew out of these Socialist clubs. As I understand it, today, the few remaining Turners are strictly sports oriented particularly in youth activities in the historic German neighborhoods. Soccer, basketball, volleyball, ice hockey and baseball have replaced calisthenics, gymnastics, fencing, medicine balls and Indian Clubs. I particularly like the advertisement for a sporting goods store inside the back cover. The proprietor is holding a fencing epee.

This piece is available for purchase here

Saturday, April 18, 2015

The Kalo Shop: 20th Century Chicago Silversmiths. In my opinion, they produced the finest studio-made, hand-wrought, arts and crafts silver in the United States.

A few weeks ago we got this lovely hand-wrought silver bowl. It is well-marked "Sterling" Hand Wrought at The Kalo Shop and N 4. It was probably a wedding or shower gift as it is also inscribed J.L September 19, 1925. This is handy as it provides a fairly accurate date for the piece.

The form of the bowl is beautiful and the hammer marks add that arts and crafts feel. Chicago as a leading producer of studio-made, hand-wrought silver had never crossed my mind so it was very interesting to learn about The Kalo Shop. I thought you might be interested too.

In addition

to pyrography and leatherwork, Barck initially sold textiles, copper items,

baskets, and jewelry. In 1905, Barck married George Welles, a coal merchant

and amateur silversmith. In 1907 she bought the house shown below to serve

as the workshop for the Kalo Arts Crafts Community in Park Ridge. When Clara

and George divorced in 1914 and the Shop moved to Chicago, George convinced

her to focus exclusively on the handwrought copper and silver items for which

it is best known. In 1912 Kalo opened a branch store in New York that lasted

only until 1916 because of war constraints (some of the date information

courtesy of Chicago metalcraft expert Darcy Evon).

In addition

to pyrography and leatherwork, Barck initially sold textiles, copper items,

baskets, and jewelry. In 1905, Barck married George Welles, a coal merchant

and amateur silversmith. In 1907 she bought the house shown below to serve

as the workshop for the Kalo Arts Crafts Community in Park Ridge. When Clara

and George divorced in 1914 and the Shop moved to Chicago, George convinced

her to focus exclusively on the handwrought copper and silver items for which

it is best known. In 1912 Kalo opened a branch store in New York that lasted

only until 1916 because of war constraints (some of the date information

courtesy of Chicago metalcraft expert Darcy Evon).

While other

silversmiths like Randahl sold co-branded products through department stores,

the Kalo Shop did not. In the late 1920s Welles tried creating several dozen

Danish-influenced items she called the Norse Line to sell through other

merchants, but the onset of the Depression ended this venture prematurely.

(Norse Line products -- usually marked with an NS in addition to the Kalo

stamp -- are rare.) The Shop had a loyal clientele that helped it thrive

through the troubled 1930s when many other silversmiths failed.

While other

silversmiths like Randahl sold co-branded products through department stores,

the Kalo Shop did not. In the late 1920s Welles tried creating several dozen

Danish-influenced items she called the Norse Line to sell through other

merchants, but the onset of the Depression ended this venture prematurely.

(Norse Line products -- usually marked with an NS in addition to the Kalo

stamp -- are rare.) The Shop had a loyal clientele that helped it thrive

through the troubled 1930s when many other silversmiths failed.

The

Kalo Shop produced handwrought flatware, holloware and jewelry, and trained

or worked with noted Chicago metalsmiths such as Julius Randahl, Grant Wood,

Esther Meacham, Matthias Hanck, Falick Novick, Heinrich Eicher, and Emery

Todd. In the early years most of the output was copper, but quickly changed

to silver. It also produced fine gold jewelry. Kalo objects have a

timeless, elegant style that seems modern today even though many pieces were

made nearly a century ago.

The

Kalo Shop produced handwrought flatware, holloware and jewelry, and trained

or worked with noted Chicago metalsmiths such as Julius Randahl, Grant Wood,

Esther Meacham, Matthias Hanck, Falick Novick, Heinrich Eicher, and Emery

Todd. In the early years most of the output was copper, but quickly changed

to silver. It also produced fine gold jewelry. Kalo objects have a

timeless, elegant style that seems modern today even though many pieces were

made nearly a century ago.

Available for purchase here

The

Kalo Shop was founded in 1900 in Chicago by 32-year old Clara P. Barck. From a January, 1901 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune:

"The

Kalo company is the latest group to be formed. It is composed of six young

women, Bertha Hall, Rose Dolese, Grace Gerow, Clara

P. Barck, Ruth Raymond, and Bessie McNeal, and their company name is taken

from a Greek word meaning "to make beautiful." They are all

graduates of the designers' course at the Art Institute, and besides

designing for wall decoration, produce articles in burnt wood and decorated

leather. The workshop of the Kalo company is in the Bank of Commerce

Building."

In addition

to pyrography and leatherwork, Barck initially sold textiles, copper items,

baskets, and jewelry. In 1905, Barck married George Welles, a coal merchant

and amateur silversmith. In 1907 she bought the house shown below to serve

as the workshop for the Kalo Arts Crafts Community in Park Ridge. When Clara

and George divorced in 1914 and the Shop moved to Chicago, George convinced

her to focus exclusively on the handwrought copper and silver items for which

it is best known. In 1912 Kalo opened a branch store in New York that lasted

only until 1916 because of war constraints (some of the date information

courtesy of Chicago metalcraft expert Darcy Evon).

In addition

to pyrography and leatherwork, Barck initially sold textiles, copper items,

baskets, and jewelry. In 1905, Barck married George Welles, a coal merchant

and amateur silversmith. In 1907 she bought the house shown below to serve

as the workshop for the Kalo Arts Crafts Community in Park Ridge. When Clara

and George divorced in 1914 and the Shop moved to Chicago, George convinced

her to focus exclusively on the handwrought copper and silver items for which

it is best known. In 1912 Kalo opened a branch store in New York that lasted

only until 1916 because of war constraints (some of the date information

courtesy of Chicago metalcraft expert Darcy Evon).

While other

silversmiths like Randahl sold co-branded products through department stores,

the Kalo Shop did not. In the late 1920s Welles tried creating several dozen

Danish-influenced items she called the Norse Line to sell through other

merchants, but the onset of the Depression ended this venture prematurely.

(Norse Line products -- usually marked with an NS in addition to the Kalo

stamp -- are rare.) The Shop had a loyal clientele that helped it thrive

through the troubled 1930s when many other silversmiths failed.

While other

silversmiths like Randahl sold co-branded products through department stores,

the Kalo Shop did not. In the late 1920s Welles tried creating several dozen

Danish-influenced items she called the Norse Line to sell through other

merchants, but the onset of the Depression ended this venture prematurely.

(Norse Line products -- usually marked with an NS in addition to the Kalo

stamp -- are rare.) The Shop had a loyal clientele that helped it thrive

through the troubled 1930s when many other silversmiths failed.

Welles

retired to Mission Hills, California in 1939. In 1959, six years before she

passed away, she turned the shop over to four of her craftsmen, Robert Bower,

Daniel Pederson, Arne Myhre, and Yngve Olsson. When

Pederson and Olsson died in 1970, the store closed for good.

In an

interview in the Summer 1992 issue of American Silversmith, Bower,

who managed the operation for its final 30 years, explained why the Shop shut

down. "We ran out of silversmiths. In the last year we lost our three

top silversmiths; men who could not be replaced. It was difficult trying to

find men willing to learn silversmithing and it took years to train

them."

The

Kalo Shop produced handwrought flatware, holloware and jewelry, and trained

or worked with noted Chicago metalsmiths such as Julius Randahl, Grant Wood,

Esther Meacham, Matthias Hanck, Falick Novick, Heinrich Eicher, and Emery

Todd. In the early years most of the output was copper, but quickly changed

to silver. It also produced fine gold jewelry. Kalo objects have a

timeless, elegant style that seems modern today even though many pieces were

made nearly a century ago.

The

Kalo Shop produced handwrought flatware, holloware and jewelry, and trained

or worked with noted Chicago metalsmiths such as Julius Randahl, Grant Wood,

Esther Meacham, Matthias Hanck, Falick Novick, Heinrich Eicher, and Emery

Todd. In the early years most of the output was copper, but quickly changed

to silver. It also produced fine gold jewelry. Kalo objects have a

timeless, elegant style that seems modern today even though many pieces were

made nearly a century ago.

Welles was

unusual for many reasons. While most other silversmiths of the period ran

smaller boutique storefronts, Welles knew from the start that she wanted a

large commercial operation. At one point she employed over 25 silversmiths.

She hired women whom she called the "Kalo Girls" to design most of

the items, and Scandinavian immigrants to fabricate them, at a time when both

of these groups were shunned by many businesses. During the first World War

silver was scarce, some of her silversmiths were sent overseas, and the

influx of foreign silversmith trainees was reduced. Welles adjusted by

having her female employees produce smaller items and jewelry. It is this pre-1920

period that was the Shop's most fertile.

After Welles

retired, the Shop continued making copies of the early pieces, adding a few

modernist items and some in the Danish taste. Many of its forms are

classics, and very collectible, reflecting Welles' motto: "Beautiful,

Useful, Enduring."

The Studio today is a private residence and pottery.

All photos and text courtesy of Chicago Silver

Friday, April 17, 2015

Leslie Ragan (1897-1972) artwork for the Chicago, South Shore and South Bend Interurban Railroad ca 1920's.

During the 1920s, the interurban Chicago, South Shore, and South Bend

Railroad, best known simply as the South Shore, hired numerous poster

artists to advertise its trains. Of these, the one who eventually became

most famous is Leslie Ragan, whose later work for the New York Central

and Budd epitomized the art of mid-twentieth-century rail paintings. Leslie was born in Woodbine, Iowa in 1897. He studied at the Cumming School of Art in Des Moines, and later, at The Art Institute of Chicago. He died in 1972. Text and photos courtesy of Streamliner Memories.

Most of these poster artists were born in the 1880s and 1890's, the only exceptions being some of the contributors to the Southern Pacific posters. I suspect the reason for this seeming coincidence is that these artists happened to come of age at a time when printing technologies had advanced enough to make it economically feasible to print larger numbers of multi-colored posters.

In an article about the South Shore’s posters, artist J. J. Sadelmeier describes how posters were printed. “Back then, the lithography process used to (re)produce these posters involved taking and artists artwork (in this case 15″X22″ water-based gouache paintings on board) and translating the designs to separate lithography stones–one for each color. The lithographer’s objective was to faithfully reproduce everything from color to texture and then register all the separate color levels during the printing process to replicate the original design. The final image was also enlarged to the standard 27″X41″ (one sheet) poster size for exterior display on the train platforms, etc.”

Ultimately, this process was replaced by modern four-color printing, which allows the reproduction of just about any color with just four passes. Four-color printing also made possible posters from photographs, which put most poster-making artists out of business.

The chief limitation of the lithographic process is that it required a separate print run for each and every color on the poster–and each print run is another opportunity to mess up. This is why so many artists made designs that were flat even though their paintings that weren’t intended to become posters tended to be much more detailed. Even these South Shore posters, which are pretty flat, require four, five, or more print runs.

Leslie Ragan was younger than the 1880s artists, having been born in Iowa in 1897. His youth allowed his career to extend well into the streamlined age, though most of his post-war work was published as magazine ads rather than posters. His work for The New York Central Railroad has become iconic in American transportation art but I really love the warmth and 1920's feel of his earlier work for The South Shore Line. They remind me very much of the woodcut prints of Hoosier and Santa Fe artist Gustav Baumann.

Here are a few examples of the work Ragan produced for The New York Central Railroad.

Most of these poster artists were born in the 1880s and 1890's, the only exceptions being some of the contributors to the Southern Pacific posters. I suspect the reason for this seeming coincidence is that these artists happened to come of age at a time when printing technologies had advanced enough to make it economically feasible to print larger numbers of multi-colored posters.

In an article about the South Shore’s posters, artist J. J. Sadelmeier describes how posters were printed. “Back then, the lithography process used to (re)produce these posters involved taking and artists artwork (in this case 15″X22″ water-based gouache paintings on board) and translating the designs to separate lithography stones–one for each color. The lithographer’s objective was to faithfully reproduce everything from color to texture and then register all the separate color levels during the printing process to replicate the original design. The final image was also enlarged to the standard 27″X41″ (one sheet) poster size for exterior display on the train platforms, etc.”

Ultimately, this process was replaced by modern four-color printing, which allows the reproduction of just about any color with just four passes. Four-color printing also made possible posters from photographs, which put most poster-making artists out of business.

The chief limitation of the lithographic process is that it required a separate print run for each and every color on the poster–and each print run is another opportunity to mess up. This is why so many artists made designs that were flat even though their paintings that weren’t intended to become posters tended to be much more detailed. Even these South Shore posters, which are pretty flat, require four, five, or more print runs.

Leslie Ragan was younger than the 1880s artists, having been born in Iowa in 1897. His youth allowed his career to extend well into the streamlined age, though most of his post-war work was published as magazine ads rather than posters. His work for The New York Central Railroad has become iconic in American transportation art but I really love the warmth and 1920's feel of his earlier work for The South Shore Line. They remind me very much of the woodcut prints of Hoosier and Santa Fe artist Gustav Baumann.

Here are a few examples of the work Ragan produced for The New York Central Railroad.

Monday, April 6, 2015

Important and early, polished, cast aluminum abstract sculpture by Dan Blue (1958-2013) Chicago, Illinois.

We picked up this piece on a house call yesterday morning. The more I learn about the artist, the more interesting the piece becomes. Dan was educated at the Art Institute of Chicago but seemingly had the mind, creativity and lifestyle of an outsider artist. This piece was executed when Dan was 18 years old. It is signed and dated 1976. For more pictures and to purchase click here

Our Urban Times, a newspaper for the Bohemian neighborhoods of Bucktown, East Village, Noble Square, Ukrainian Village, WestTown and Wicker Park provided a beautiful obituary.

UPDATE Jan. 6:

The Chicago Police Detectives indicated that they are waiting for a toxicology report which can take up to 6 weeks but there is no indication of foul play.

Described as sculptor, raconteur, friend, brother and man of mystery, Daniel Blue is dead at the age of 55. Resident in an industrial building east of Elston and near the Hide Out, Dan was found in his home Jan. 2. The cause of death has not been determined. There will be a memorial service at some point but no plans have been established.

His unexpected passing has his family, friends and colleagues in a

state of shock. As they each talk about him, they all express many of

the same feelings... respect, admiration, appreciation, affection, love

and a terrible sense of loss. The kind of loss that opens a gaping hole

in the middle of your being.

His unexpected passing has his family, friends and colleagues in a

state of shock. As they each talk about him, they all express many of

the same feelings... respect, admiration, appreciation, affection, love

and a terrible sense of loss. The kind of loss that opens a gaping hole

in the middle of your being.

Dan was the middle child born to the late Donald and Ruth Blue, Cindy

was the eldest and Tom the youngest. They grew up in Northbrook and

attended Glenbrook High School. Dan continued his education at the Art

Institute of Chicago.

"Big Blue, that was our nickname for him, was a great brother. We would pick on each other, but he was always there to make sure I was ok," said Tom. "As kids we were always outside having crazy fun. We played kids games that we made up with other neighborhood kids. Nobody would get hurt, it was kid stuff.

"He was at the Art Institute of Chicago for only two years because the instructors felt they had no more to teach him. He had already purchased the machines he needed so he went off on his own. Later he spent another two years as an apprentice for other sculptors.

"Being an artist, he was on his own creative time schedule, often having many projects going at same time. He stepped back from his artwork for awhile. He decided to put his own life on a back burner to try and help others. He was a good friend to those he cared about and wasn't afraid of speaking up to others. He avoided the spotlight."

Part owner in the Sedgwick Studio, a former CTA sub-station structure in Old Town, Tom Scarff brought Dan into the studio.

Part owner in the Sedgwick Studio, a former CTA sub-station structure in Old Town, Tom Scarff brought Dan into the studio.

"He came to my studio when he was 18. He was a talented genius, a hard worker. He was always creating and making something better. He was like a son without the blood connection.

"Dan loved kites, the crazier the better. One night he brought out [to Indiana] a huge kite. It was a foggy night we were on the beach. He attached a flare, that burned for 20 minutes, to the kite string and it sailed up high over head. Suddenly every path in the area had beams of flashlights. A friend of mine had his Russian Wolfhound with us too.

"The police, who received about 50 UFO reports, were part of the

parade of flashlights. When they encountered the Russian Wolfhound they

were convinced they had found the aliens! We assured them that we had

meant no harm, just having some fun. As they left, they turned to Dan

and said, 'Please don't do that again.'

"The police, who received about 50 UFO reports, were part of the

parade of flashlights. When they encountered the Russian Wolfhound they

were convinced they had found the aliens! We assured them that we had

meant no harm, just having some fun. As they left, they turned to Dan

and said, 'Please don't do that again.'

"I'll never see another kite without thinking of Dan."

Another one of Dan's partners was John Adduci. According to him, they also formed Adduci Blue, Inc. in the early 80s. "We fabricated other sculptors' works for about four years. Dan was a great nuts-and-bolts guy, a fine craftsman. As a person, he was a perfect gentleman. He was polite and went out of his way to be a good guy." Among the sculptors for whom they fabricated was Jerry Peart, another former partner in the Sedgwick studios.

Dan's own work can be seen in Northbrook (above), in Kenosha, WI, and in Chicago.

Our Urban Times, a newspaper for the Bohemian neighborhoods of Bucktown, East Village, Noble Square, Ukrainian Village, WestTown and Wicker Park provided a beautiful obituary.

In memory of Daniel Blue: A patchwork of facts, respect, admiration, appreciation, love and affection

By:

Elaine Coorens

Date:

01/04/2013 The Chicago Police Detectives indicated that they are waiting for a toxicology report which can take up to 6 weeks but there is no indication of foul play.

Described as sculptor, raconteur, friend, brother and man of mystery, Daniel Blue is dead at the age of 55. Resident in an industrial building east of Elston and near the Hide Out, Dan was found in his home Jan. 2. The cause of death has not been determined. There will be a memorial service at some point but no plans have been established.

His unexpected passing has his family, friends and colleagues in a

state of shock. As they each talk about him, they all express many of

the same feelings... respect, admiration, appreciation, affection, love

and a terrible sense of loss. The kind of loss that opens a gaping hole

in the middle of your being.

His unexpected passing has his family, friends and colleagues in a

state of shock. As they each talk about him, they all express many of

the same feelings... respect, admiration, appreciation, affection, love

and a terrible sense of loss. The kind of loss that opens a gaping hole

in the middle of your being."Big Blue, that was our nickname for him, was a great brother. We would pick on each other, but he was always there to make sure I was ok," said Tom. "As kids we were always outside having crazy fun. We played kids games that we made up with other neighborhood kids. Nobody would get hurt, it was kid stuff.

"He was at the Art Institute of Chicago for only two years because the instructors felt they had no more to teach him. He had already purchased the machines he needed so he went off on his own. Later he spent another two years as an apprentice for other sculptors.

"Being an artist, he was on his own creative time schedule, often having many projects going at same time. He stepped back from his artwork for awhile. He decided to put his own life on a back burner to try and help others. He was a good friend to those he cared about and wasn't afraid of speaking up to others. He avoided the spotlight."

Part owner in the Sedgwick Studio, a former CTA sub-station structure in Old Town, Tom Scarff brought Dan into the studio.

Part owner in the Sedgwick Studio, a former CTA sub-station structure in Old Town, Tom Scarff brought Dan into the studio."He came to my studio when he was 18. He was a talented genius, a hard worker. He was always creating and making something better. He was like a son without the blood connection.

"Dan loved kites, the crazier the better. One night he brought out [to Indiana] a huge kite. It was a foggy night we were on the beach. He attached a flare, that burned for 20 minutes, to the kite string and it sailed up high over head. Suddenly every path in the area had beams of flashlights. A friend of mine had his Russian Wolfhound with us too.

"The police, who received about 50 UFO reports, were part of the

parade of flashlights. When they encountered the Russian Wolfhound they

were convinced they had found the aliens! We assured them that we had

meant no harm, just having some fun. As they left, they turned to Dan

and said, 'Please don't do that again.'

"The police, who received about 50 UFO reports, were part of the

parade of flashlights. When they encountered the Russian Wolfhound they

were convinced they had found the aliens! We assured them that we had

meant no harm, just having some fun. As they left, they turned to Dan

and said, 'Please don't do that again.'"I'll never see another kite without thinking of Dan."

Another one of Dan's partners was John Adduci. According to him, they also formed Adduci Blue, Inc. in the early 80s. "We fabricated other sculptors' works for about four years. Dan was a great nuts-and-bolts guy, a fine craftsman. As a person, he was a perfect gentleman. He was polite and went out of his way to be a good guy." Among the sculptors for whom they fabricated was Jerry Peart, another former partner in the Sedgwick studios.

Dan's own work can be seen in Northbrook (above), in Kenosha, WI, and in Chicago.

Thursday, March 26, 2015

Friday, January 9, 2015

Lee Godie, American (1908-1994)

If you worked, went to school or hung out on the south end of The Loop in the 1970's you probably saw Lee Godie peddling her paintings. We had the good fortune of selling 5 pieces by this Chicago outsider artist. The person we acquired them from was a student at the Art Institute of Chicago and Lee used to hang out by the loading dock where the students all smoked. Many times she would trade art for cigarettes.

Lee Godie (1908–1994) was an American self-taught artist who lived most of her life in Chicago. Lee Godie was born Jamot Emily Godee. She later married and had four children, but following the death of two of her children and the failure of her two marriages she found herself living on the streets of Chicago. Godie could be seen on the steps of the Art Institute of Chicago arriving on the scene in 1968 selling her canvases to passerby. She worked in a variety of mediums which included watercolor, pencil, tempera, ballpoint pen, and crayon and on a number of surfaces such as canvas, poster board, sheets of paper and discarded window blinds. Some of her works were several pieces stitched together in the fashion of a triptych or book. Also included in the array of art works Godie created are the black-and-white snapshots from photo booths she took of herself dressed up in different personae. She would take these photos and embellish certain parts of them, adding color to her lips or nails or painting on darker eyebrows.[1]

Godie was a self-styled French Impressionist with the belief in her work as being as significant as Paul Cézanne.[2] She was particular about who she sold her art to and even to whom she talked to. Her fashion style was just as unique as her personality, and she could be seen wearing different swatches of fabric wrapped around herself or fur coats that were pieced together.

Lee Godie remained in downtown Chicago for almost a 30-year period, becoming a facet to the social milieu during that time. Eventually Godie was reunited with her daughter Bonnie Blank, who moved her out to the suburbs to live with her. On August 28, 1991, Chicago’s Mayor Daley proclaimed September “Lee Godie Exhibition Month”. [3] Between November 13, 1993 and January 16, 1994, an exhibition entitled "Artist Lee Godie: A Twenty-Year Retrospective", curated by Michael Bonesteel, who wrote the "Lee Godie" article in Raw Vision magazine, was presented at the Chicago Cultural Center. From September 12, 2008 to January 3, 2009, an exhibition of over 100 pieces of Lee Godie’s work entitled “Finding Beauty: The Art of Lee Godie” was on exhibit at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art. Her work can be found in the permanent collections of the Museum of American Folk Art in New York City, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Arkansas Arts Center and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. (courtesy of Wikipedia)

#leegodie

#outsiderart

#outsiderart

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)